Modern Westerners shy away from blood and hide the corpses of our dead in hospitals and funeral homes. Even death row inmates are executed quietly and behind closed doors with as little blood or gore as possible. But there are societies that have done the opposite. Far from shying away from death, they have sought it out. Cultivated it. Made it a public spectacle. Human sacrifice is surprisingly common in ancient history. But perhaps no culture did it on the scale of the Aztecs.

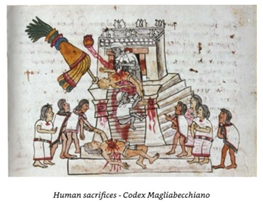

Picture a priest standing on pyramid stairs. In front of him is a young man captured in war, drugged to pacify, painted and oiled. The priest takes the dangerously sharp obsidian blade, cuts open the chest of the man, and rips out a still-beating heart. He turns and raises it up to the sky and then turns to show it to the crowd below. Imagine the smell. The blood. The horror you might feel upon seeing this in person. Now imagine this not as a one off horrific event but as a production line of butchery. Imagine that just this day, around 700 victims would suffer the same fate. And 700 tomorrow. And the next. All year.

In The Return of the Dragon, I wrote about how many societies took drugs for spiritual purposes, encountered serpent deities, and then practiced human sacrifice. In this article, I would like to focus on one such case: the Aztecs. This Mesoamerican culture dominated central Mexico from the early fourteenth century until Cortes arrived in the 16th. They are known for their beautiful architecture and technology. When the Spanish arrived they described Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire, as a Venice of the New World. Its beautiful canals operated like roads that crossed throughout the vast city that stood in the shadows of great and beautiful pyramids.

But the Spanish quickly learned something dark cast a shadow over this beautiful city. They observed the unholy Trinity of psychotropic drugs, visions of serpents, followed by brutal human sacrifice.

Taking Mushrooms

Consider this passage from the Spanish explorer Diego Duran,

“All the lords and principal men of the provinces rose and, in order to make the festival even more solemn, ate wild mushrooms that are said to make a man lose senses. In that way they then went out to dance… On the day called Cipactli, which was the first day of the month, represented as a kind of serpent’s head, and which always was the day when kings were enthroned, all the prisoners taken in Metztitlan (even though they are few in number) were taken out and sacrificed on the Sun Stone.”

The Aztecs ate the mushrooms. They celebrated on the day of the serpent (many of their gods were serpents), then they became violent and searched for humans to sacrifice.

Worshiping Serpent Entities

After taking the mushrooms, they would see snake entities. As Friar Motolinia stated in 1540:

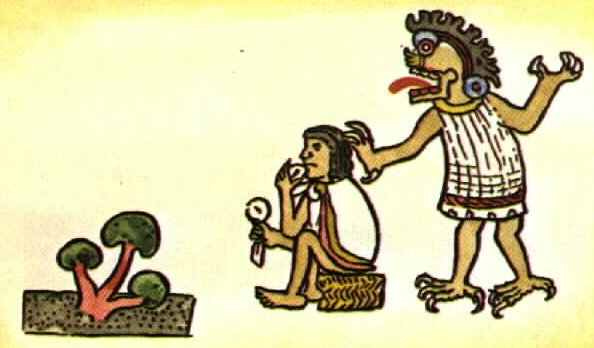

“They had another way of getting drunk that made them crueler: it was with certain fungi or small mushrooms (unos hongos o setas pequeñas), of which there are such in this land as in Castile; but those of this land are of such quality that eaten raw and being bitter, they drink after taking them and eat them with a little bee honey; and in a little while they see a thousand visions and especially snakes; and as they go out of their senses, their legs and body appear full of worms eating them alive and thus half raving they leave the house wanting someone to kill them…”

So they took the mushrooms and saw snakes. Is it then a coincidence that the gods they began to worship were also snakes? They worshiped Quetzalcoatl (Plumed Serpent) who was the god of the morning star, the lord of the star of the dawn, the giver of maize corn to mankind, the inventor of books and the calendar, and a symbol of death and resurrection. He was the patron of the priests. They also worshiped Ciuacoatl (Snake-woman) the god of motherhood and midwives. She helped Quetzalcoatl create the current race of humanity by grinding up bones from the previous ages, and mixing it with his blood. Ciuacoatl was the mother of Mixcoatl (cloud serpent), the god of the hunt. And then there was Chicomecōātl (seven serpent) was the goddess of agriculture. Many other serpent gods were worshiped as well.

Sacrifice

The gods witnessed on mushrooms gave great knowledge to those who would listen. The skills learned in architecture, agriculture and war allowed the Aztecs to rule the neighboring tribes and build one of the world’s great empires. But the serpent gods also had dark demands. In order to appease the gods and partake of the promises they offered, sacrifices in the most literal sense had to be offered. And like perhaps no other known culture they were offered in earnest. Scholars estimate as many as 250,000 men, women and children were offered up every year. Conquistador Andrés de Tapia described the way the sacrifices helped build the Aztec empire. He said that the Aztecs had two rounded towers flanking the Templo Mayor made entirely of human skulls. Between them, he wrote, a towering wooden rack displayed thousands more skulls impaled on wooden poles. The architecture of the Aztecs was literally built with human sacrifice.

Below is a graphic recently published in Science that recreates the towers that de Tapia described.

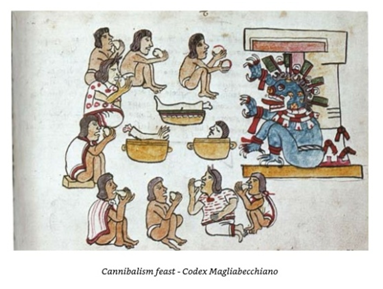

The depravity often extended beyond the sacrifice itself and was followed by cannibalism.

When we see a society like the Aztecs, we must ask, ‘how did they get that way?’ How do human beings grow to accept something that seems so far from what is right and good? How do humans butcher and destroy their fellow humans with so little remorse or sense of guilt? It would be impossible to blame it on the era (many cultures of the era practiced no such butchery) or something inherent in the people themselves (their decedents live peacefully today). So what was it? According to Spanish observers, the cause was simple: they took mushrooms, saw serpents, and violence followed.

In 21st century America, similar psychedelics are popular again. They are laughed off as harmless or even beneficial. But the point of my book and the point of this article is to challenge those assumptions. Perhaps the effects of the mushrooms are not so easily detected and perhaps with time and with broader societal acceptance more frightening effects might come to light.

In the Return of the Dragon, I reviewed so many cultures throughout the world that engaged in drugs for spiritual purposes (pharmakeia), serpent worship, and human sacrifice but it may be the Aztecs that best represent this pattern. Their use of mushrooms, their visions of serpents, and their dark response to the visions is shocking and disturbing but also a warning to future generations. Sadly, it is a warning that few appear to be hearing.

Endnotes/Credits:

Jan Irvin’s “God's Flesh: Teonanácatl: The True History of the Sacred Mushroom” was a helpful source of some of the quotes here.

Also, Science Magazine’s “Feeding the gods: Hundreds of skulls reveal massive scale of human sacrifice in Aztec capital” by Lizzie Wade was very helpful.

While your argument is compelling, how would you differentiate between the ritualistic use of psychedelics, which was deeply intertwined with the Aztecs' religious beliefs and practices, and the therapeutic use of these substances in a scientific context aimed at treating mental health disorders?

The Aztecs' use of psychedelics could indeed be considered a form of pharmakeia, a term used in the Bible to refer to sorcery or the use of drugs in religious rituals. However, would the therapeutic use of psychedelics, which involves controlled dosages administered under the supervision of healthcare professionals, fall under the same category?

I look forward to hearing your thoughts on this matter.

Very peculiar carry on and completely at odds with anything I’ve personally experienced with psychedelics.