Did the Early Church Suppress Other Gospels?

Every now and then someone confidently tells me that the early church destroyed the real story of Jesus by burning and destroying alternative gospels While this claim usually comes with a lack of specificity, when pressed people will sometimes point to the "Gospel of Thomas" or one of the other "gospels" from the Nag Hammadi library. The Nag Hammadi library (also known as the "Gnostic Gospels") is a collection of texts discovered shortly after the end of the Second World War near the Upper Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi.

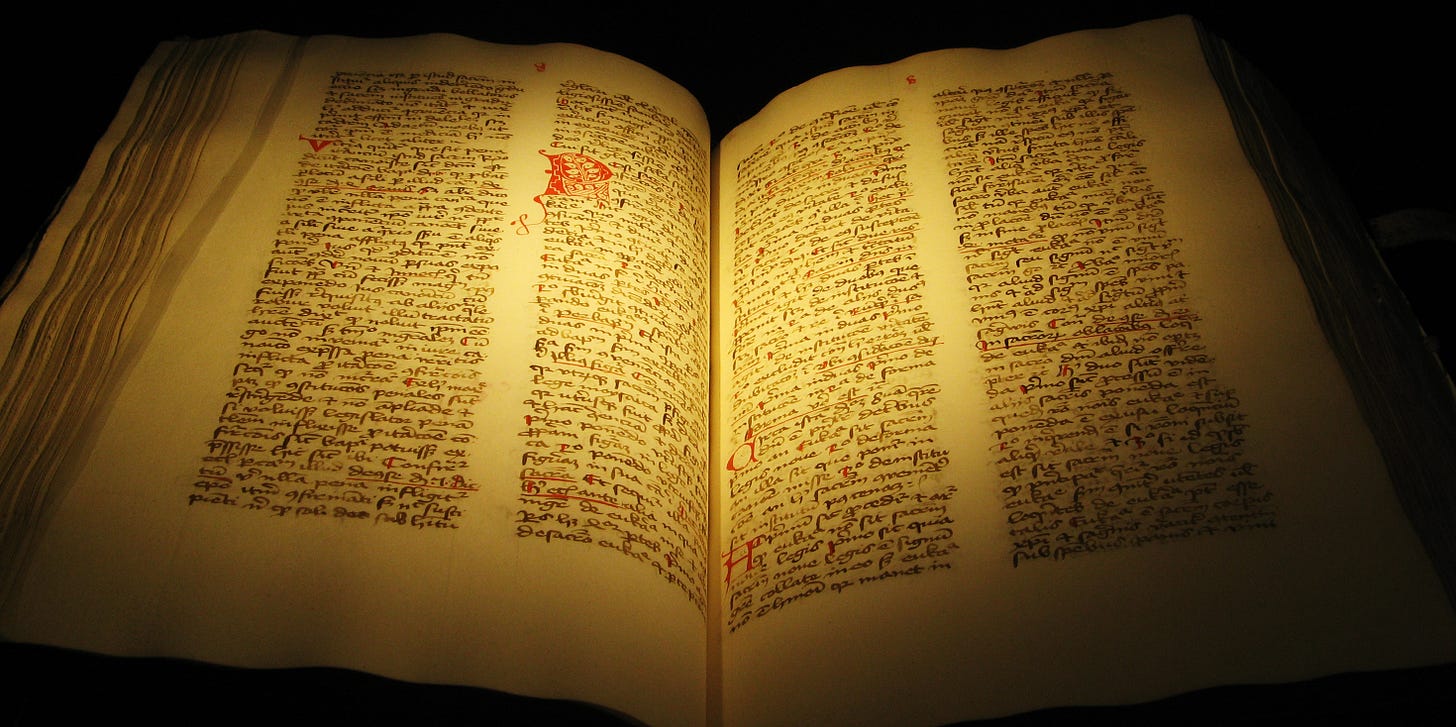

The Nag Hammadi discovery sent shock waves through the Western world as scholars came to realize that the treasure of books represented an extensive amount of lost literature belonging to a group of early mystical and esoteric Christians declared to be heretical by church fathers. It is thought that these books were buried in the wake of a declaration by 4th century church leaders including Saint Athanasius that the use of non-canonical gospels should be condemned.

Among the books of the Nag Hammadi Library, the only complete work is known as the 'Gospel of Thomas'. The book is quite different from the gospels of the New Testament canon. Unlike those, it contains mostly a list of sayings of Jesus absent a narrative. And unlike the canonical gospels, Thomas avoids the often confusing debates that Jesus had about fine points of the Jewish law, to what extent the Jews should obey their Roman rulers, and Jew/Gentile relations. Instead, the Jesus found in Thomas is one that speaks profound statements of religious truth encouraging his hearers to look within themselves for knowledge. “The one who seeks," Jesus says, "should not cease seeking until he finds."

Contrast this with the Jesus found in the four biblical gospels. We see him debating Pharisees on what is allowed on the Sabbath (Luke 6), debating whether Jews should pay taxes to Romans (Matthew 22), and making obscure rebukes to the regional ruler (Mark 8). We get narrative that shows obscure locations around the region of Galilee and later Jerusalem. We hear specific names of Jewish people whose import has been lost to history. In short, when we think about what a holy book should look like, Thomas fits the part. Matthew, Mark, and Luke (and to a lesser degree John) don't.

So then the question comes, was the church right to reject Thomas (and the other Gnostic works) and keep the now canonical gospels? Should they have kept them all? Do they contain helpful information about Jesus? By rejecting them, are we rejecting genuine historical information about Jesus?

The short answer is no. There are a number of good reasons we can be very confident that the Gnostic Gospels are later than the canonical gospels, largely based on material within the canonical gospels, and almost certainly a distortion rather than a clarification of actual first century events.

Perhaps the number one 'tell' that the Gnostic Gospels are a later and less accurate account of the life of Jesus is that they are distinctively pagan in their construction and make up. Few scholars deny that Jesus and his earliest followers were Galilean Jews from the first century. And we know quite a bit about Jewish literature from this period of time.

We know that Jewish literature of this period was heavy on narrative. Consider the works of Tobit [3rd century B.C.], 1 and 2 Maccabees [2nd century B.C.], and Judith [2nd century B.C.]. And as we have seen, all four canonical gospels come in narrative form. We know that prior to the the end of the first century, the Jewish faith was centered around temple worship in Jerusalem. And we see the Temple at the center of many of Jesus' debates and controversies (consider Matthew 21 for example). And we can surmise that they would be interested in the politics and goings on in the region. Again, we see exactly this in the four gospels of the New Testament - consider John the Baptist's ill fated clash with the regional King Herod in Matthew 14.

Now contrast these features with what we have seen in the Gospel of Thomas. The narrative has been almost completely removed (it reads more like a series of wise aphorisms). Gone are the discussions on the temple. Gone are the discussions on the first century controversies. Gone are the names of regional rulers and people of importance. Gone is the distinctively Jewish nature.

Which is more likely? That distinctively Jewish accounts of Jesus would be taken and paganized as the faith spread from Israel to the pagans throughout the Roman Empire or that a paganized account would be taken and made more Jewish in nature? The answer is obvious.

There are other reasons to be confident that Thomas is much later than the canonical gospels. For example, various verses are clearly redactions and harmonizations of the canonical gospels (consider sayings 10 and 16 in Thomas being clearly based on a harmonization of Luke 12:49, 12:51–52 and Matthew 10:34–35). It is clear that Thomas followed these canonical texts because he bases his own text on them.

And a final clue is that we have very early references to all four canonical gospels in Christian literature. By the mid second century we see all four of them being referred to and quoted. In contrast, we see no references to passages distinctive to Thomas or to the document as a whole.

So we can see that the early Christian Church did not make a mistake in rejecting Thomas and the rest of the works found at Nag Hammadi. The church had a standard for determining the canon of the New Testament: the works must either be authored by an apostle or have a very close connection with the apostles. For all the reasons we have reviewed above, the canonical gospels at least pass the smell test on this standard. They are closely connected to first century Judaism in the region. And we see that there are very good reasons to suppose that the Gospel of Thomas and the other Gnostic works do not meet this standard and were clearly compiled and composed by people separated by time, geography, and culture from the first century Jewish world that Jesus and the Apostles were born into.